In January this year, the official Melbourne meteorological observatory shut its ventilated doors and moved up the road, from the corner of La Trobe and Victoria Streets to Olympic Park. Moving a white box and some scientific instruments might not seem like a big deal, but the 2km move marks the end of a long chapter in Melbourne’s 180-year meteorological history.

Settlers’ thermometers

The earliest weather observations for Melbourne come from one of its founders, John Pascoe Fawkner. He set up camp near the corner of what is now Collins and William Streets, only two short months after the city’s other founder, John Batman, first arrived in Port Phillip Bay.

While he was claiming the city as his own, Fawkner was also recording the temperature recorded the temperature, frost and rain details in his diary. For example the 24th of November 1835 ‘came on to rain and rained heavily from about 4:30…and put the house and store in a most deplorable state’. Unfortunately Fawkner kept the thermometer inside, rather than outside in the shade, so his temperature observations don’t accurately capture Melbourne’s first summer of European settlement.

The next available weather observations are temperature data from October–December 1837 taken by Dr Patrick Cussen as a part of the “Daily Register of the Health of the Settlement”. Physicians in the 18th and 19th centuries often recorded temperature observations as part of their duties, thanks to the Hippocratic idea linking health directly to the climate.

Official records begin

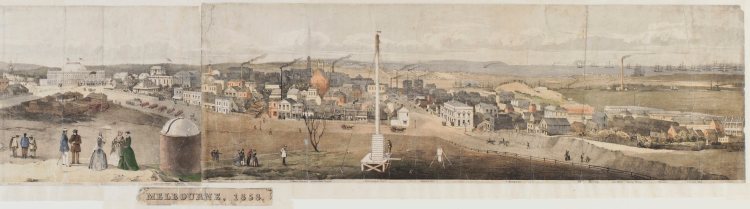

In 1839 the Colonial Office in England requested that all British colonies set up meteorological stations along their coastlines to improve understanding of the weather, and in doing so reduce deaths at sea. The New South Wales Governor George Gipps quickly organised observatories at Port Macquarie on the north coast on New South Wales, Port Jackson at the southern entrance to Sydney Cove, and at the Flagstaff Hill signal station in Port Phillip (which was part of New South Wales until 1851). This collection of stations was the first organised meteorological network in Australia.

The observatories were reportedly equipped with all the latest recording instruments and devices and the thermometer was kept in consistent conditions. These were not the same conditions that the Bureau of Meteorology have today, but they were a scientific improvement on Fawkner’s dank cellar. This means that while we can’t use the observations to say the precise temperature or rainfall on a particular day, they can tell us a lot about the year-to-year changes in Melbourne’s weather and climate, which is important for understanding our climate drivers like the El Niño–Southern Oscillation.

Observations of temperature, wind and atmospheric pressure were taken four times a day from July 1840 until the end of 1851. Rainfall was recorded daily, and monthly averages published in the Government Gazette. The observations capture Melbourne’s only recorded snowfall in August 1849, and heavy rainfall events that match stories of flooding reported in the local papers. You can see these slices of history for yourself: they are available online through the State Library of Victoria.

The weather and the stars

But in 1851 the Port Phillip observations ended, and Melbourne’s weather knowledge plunged into darkness. Government papers mention a meteorological and astronomical record maintained by local astronomer Robert Ellery at the signal station in Williamstown beginning in 1853; however these observations are yet to be found.

By April 1855, the Victorian government had resumed official observations at Flagstaff Hill under the direction of civil servant Robert Brough Smyth. The station moved in 1857 to the Public Office Grounds on Latrobe Street near the corner of William St. Smyth’s daily observations continued there until June 1858.

In 1858 the highly qualified Dr Georg Balthasar von Neumayer arrived in Melbourne from Bavaria and was appointed the Director of the Flagstaff Hill Magnetic and Meteorological Observatory in early 1859. Neuymayer was a passionate scientist who was interested in meteorology, astronomy, oceanography and surveying.

During his five-year stay in Australia, Neumayer took exhaustive meteorological and astronomical observations in Melbourne, continuing the close connection between colonial studies of astronomy and meteorology. Ellery took over from Neumayer when he returned to Germany in 1863 and Melbourne’s weather station moved again to the observatory next to Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens.

The Government Astronomer and his assistants dutifully recorded the weather in South Melbourne until the Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology was formed in 1908. Melbourne’s weather record packed up its bags once more for the little triangular garden on the corner of La Trobe and Victoria Street. This location was very close to the Bureau of Meteorology Central Office, in the aptly named Frosterly building at 2 Drummond St, Carlton.

Why modern science still cares

As you can tell, the story of Melbourne’s meteorological history can be spied all over the city. But it is more than just a particularly niche treasure map. Long-term instrumental weather records are the key to understanding our past, present and future climate.

Knowing when and where weather observations were taken is crucial for determining reliable they are. A thermometer kept next to a baking hot brick wall for example, or a rain gauge that is protected by a big tree, is not going to accurately capture the weather conditions of the surrounding atmosphere. In Melbourne’s case, surrounding sky scrapers had a large impact on the wind observations recorded at the La Trobe Street site, meaning that Melbourne’s wind observations were coming from the airport for the last few years.

When weather stations move, this can also cause gradual changes or big jumps in the data that are not due to changes in the actual climate. Statistical methods known as homogenisation techniques are used to find these jumps and reduce their influence on the long-term climate record. It is worth noting that our analysis of 1860–2012 temperature data did not find any significant impact on the temperature record when the station moved in 1908. The best way to manage this is to make observations at both the old and new locations, to determine the difference between them. The Bureau have done this for the Melbourne site, with 18 months of overlapping data.

The old La Trobe St site is owned by the Royal Society, and is now accepting suggestions for future use. One of the ideas is a museum dedicated science in Victoria. Hopefully the little triangle of grass will receive it’s own plaque, honouring it’s role in the story of Melbourne’s meteorological history.

Further reading if you’re interested

Annear R. 2005. Bearbrass: imagining early Melbourne. Black Inc., Melbourne, 255 pp. A great read about Melbourne’s early years.

Ashcroft, L., Gergis, J. and Karoly, D.J., 2014. A historical climate dataset for southeastern Australia. Geosciences Data Journal, 1(2): 158–178, DOI: 10.1002/gdj3.19. More details on the actual data, instant classic.

Billot C P, ed. 1982. Melbourne’s missing chronicle: being the Journal of preparations for departure to and proceedings at Port Phillip by John Pascoe Fawkner. Quartet Books, Melbourne, 108 pp. Fawkner’s diary

Gentilli J. 1967. A history of meteorological and climatological studies in Australia. University Studies in History 5: 54–88. An excellent summary of Australia’s meteorological history

Linforth D J. 2011. Melbourne’s early rainfall records. Bulletin of the Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society 24: 102–104. More details about the techniques and locations used to observe rainfall in Melbourne.

Rosel M. 2011. The resurrection of Philip Hervey. Weather News 345: 2–10. The hunt to discover the observer at Flagstaff Hill, only available from the Bureau of Meteorology.

Or get in touch if you would like more info.

So glad that there existed such a great legend. I have always been a weather enthusiast myself since I was a teenager. Thanks

LikeLike

Very interesting post and all of these legends were so passionate about weather.I lived in Melbourne, but never tried to know this type of weather observation history. I bookmark this page for my future.

LikeLike

Very interesting post and all of these legends were so passionate about weather. I lived in Melbourne, but never tried to know this type of weather observation history. I bookmark this page for my future use.

LikeLike